Not in Kansas Anymore

A century ago, amidst the poultry and pig farms in a small corner of Kansas, a local doctor became inundated with cases of a peculiar strain of pneumonia and flu. One such case was that of a soldier at Fort Riley, who, on March 3rd, 1918, approached his superiors and informed them that he felt feverish. By noon of the same day, hundreds of more soldiers reported similar symptoms. They could not have known that the disease they carried would take more lives than the war they were fighting ever had.

These soldiers were the perfect victims of a unique pandemic, which for reasons still unknown, disproportionately affected the young. As they dwelt in packed barracks, trenches, and the prisoner of war camps of World War I, they found themselves in the ideal hunting ground of the Spanish flu. Many carried it with them as they crossed the globe in dizzying numbers, shuttling back and forth from the front lines.

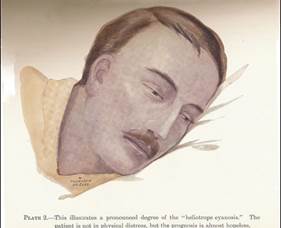

As soon as the first cases were reported in America and China, the death toll began to mount. The ‘Spanish Lady’ was an extremely efficient assassin. It would begin with little fanfare, a simple fever. Within days, however, victims would be bleeding from the nose, stomach and intestines, with fluid filling their lungs and starving them of oxygen. Most would ultimately succumb to pneumonia, by which time their bodies would have turned purple and blue. Whilst it is reported that 1/3rd of the world was infected, and 50-100 million people died, it is impossible to know the true count, as many cases were attributed solely to pneumonia, or simply to ‘war’.

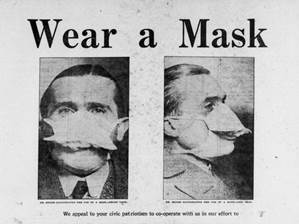

Left: The so-called ‘purple death’. Right: A ‘mask’ of some sort.

Any initial passivity soon passed, as it became progressively clear that this new ailment was both extremely contagious and deadly. Across the globe, masks were encouraged, and individual cases quarantined, in measures recognisable to us today. Without these measures, it would certainly have been worse. Despite their best efforts, however, the war complicated matters immensely. Many medical personnel were stationed abroad, unable to return promptly, and in increasingly dire field hospitals, they were left just as susceptible as the soldiers they were treating. Hospitals at home were thus understaffed, and they would only be more so as the available doctors and nurses died in droves. There were not enough healthy gravediggers to bury the dead, and victims would often be buried in unmarked or mass graves. It is a cruel irony that even the eventual armistice would cause deaths; afflicted soldiers would carry the Spanish flu to their own communities, stranded refugees would carry it to their new homes, and large celebratory gatherings would encourage its spread.

As with the Liberty Loan Parade in Philadelphia, we now know that these public gatherings endangered all who participated, but they were then seen as completely innocuous. In fact, it was the policy that allowed for these events to be held, that also allowed for fan-attended football to continue. Contrary to current belief, the commonly held theory of the time was that circulated, open-air would keep you perfectly safe. So, in the midst of one of the deadliest pandemics in history, tens of thousands of fans attended football matches under open skies.

It is impossible to know what effect this had on the spread of the flu, but this situation, both too familiar and highly unprecedented in modern times, certainly made for some fascinating stories. This article will cover those stories of players, games, and seasons, shaped by this particular moment in history.

– – –

Spain

That the 1918 influenza came to be known as the ‘Spanish Flu’ is an unfortunate consequence of the neutrality of Spain’s reporting system, which had no wartime censorship restrictions. Whilst other countries limited the spread of information in order to control morale, Spanish papers were able to freely report on case numbers, deaths, and on the most prominent case in Spain, that of King Alfonso XIII. It thus appeared at the time that Spain had been hit the hardest. We now know this was probably untrue, but they, like all others, certainly suffered. 300,000 people would ultimately die in Spain.

Early on, however, in Spanish media as elsewhere, the flu was being dismissed. The greatest precaution suggested was to occasionally gargle with salt water. It was in this early stage of the pandemic that King Alfonso XIII fell gravely ill with the flu. It was also in these circumstances that 2 matches were scheduled between FC Barcelona and Madrid FC (now Real Madrid).

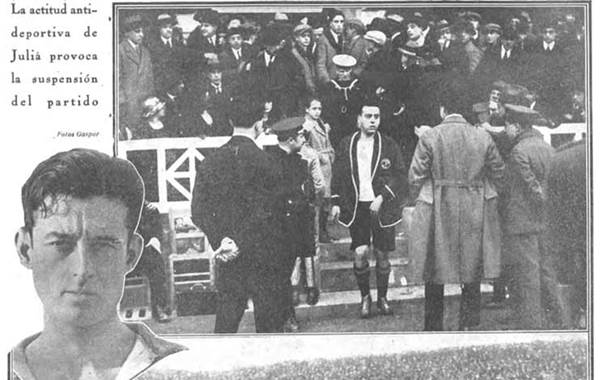

The first game was played on Friday 17th May 1918, with Josep Juliá and Vincenc Martinez scoring for Barcelona in a 2-1 win.

The second game was scheduled to be played 2 days later. That morning, however, Joan Gamper, famed founder of Barcelona, sought out the Madrid board. He carried with him a certificate from Dr D. Joan Horma González, stating that an influenza had spread through 8 of their players, causing a flu-like chest problem. The Spanish flu had arrived in Barcelona.

Among the 8 afflicted were some of the most important players of Barcelona’s early years and contributors to their first golden age in the 1920s:

Gabriel Bau (1892-1944) was ‘the great captain’ of the Catalan national team. Reports of the time suggest he was a good, solid player, without being truly spectacular. His greatest asset was his ability to play in defence and midfield, though he was best as an attacker; indeed, in the 1914/15 season, he had outscored Paulino Alcántara.

Paulino Alcántara (1896-1964) remains the club’s second highest scorer, with an incredible 395 goals in 399 games. The Filipino was nicknamed ‘the netbreaker’ as on the 30th April 1922, in a game against France, he hit a shot so hard it ripped right through the net. His legacy is somewhat tarnished by his having volunteered with the troops of both Franco and Mussolini, his association with the ‘Butcher of Badajoz’, and his general support of various fascist groups.

Agustí Sancho (1895-1960) was a short but fast midfielder who would play a crucial role for FC Barcelona in the coming years. Reports praise his speed, marking, and presence on the pitch: ‘He gave everything he had on the pitch, to the extent that he’d even yell at his opponents if he didn’t think they were pulling their weight. “If you don’t want to fight, then I’ll do it alone!” he famously yelled on one occasion’.

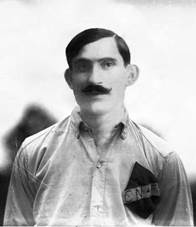

Vincenc Martinez (1896-1963) remains one of the greatest scorers in club history. Known as ‘cabecita’ (little head, see picture), he played around 270 games and scored around 200 goals. We have no information on how many of those goals were headers. Of the 8, he was the most affected by the flu.

Josep Juliá (1895-1973) was a right back who played 48 games for the club and scored 22 goals. 6 years after this game, he would retire in bizarre circumstances. With Barcelona up by 1 in the 38th minute, Juliá was sent off but repeatedly refused to leave. After further argument, the game was abandoned, and victory was controversially given to Barcelona. Juliá was suspended for a year, but decided to retire instead.

The final three were Francesc Viñals (1897-1951), Josep Costa (1894-1968) and Carlos María Rovira, one of the first Argentines to play for the club.

Upon hearing of their illness, multiple men from the Madrid board decided to go to the hotel to see for themselves. Some newspapers of the time suggested this was an act of fellowship, whilst others suggested it was an act of suspicion; some claimed Madrid were lucky to avoid playing the match as they would thus be spared another defeat, others mocked Barcelona for being unable to deal with a ‘simple’ flu, reflective of the attitude towards the flu in its early stages. The board confirmed their illness, and hurriedly arranged a match against a different opponent. Madrid would win the match 6-2, with a certain Santiago Bernabéu scoring a hattrick.

Barcelona spared no expense in ensuring the comfort of their players on the return journey, with Gamper paying over 3000 pesetas on train tickets. The club was fined for not playing the game as scheduled. They would similarly have to cancel their next match. By June 2nd 1918, all but Martinez had returned, though he too would return the following week.

In these few short weeks between their affliction and recovery, attitudes in Spain had been made to change, as it became abundantly clear this was no ‘simple’ flu. Cases and deaths were rapidly rising. This had little direct impact on the footballing world, which, as a consequence of the open-air policy, continued as before with only a few stops and starts.

Iberia SC (now Real Zaragoza) had played their last game on September 29th against CD Fuenclara, winning 13-0. By the time they returned, winning 7-0 on November 1st, 4000 people in the local area had died, and around 10,000 had died in the larger region. Bilbao had been struck particularly badly, so Athletic Bilbao organised a benefit match, with all proceeds going to a fund for Spanish flu victims in the area, and their families.

On October 17th 1918, 46 people died of the flu and related complications in Barcelona. That very day, Joan Gamper appeared before the board of the Catalan Championships and presented the open-air argument. The board was persuaded, and the Championships, the first league in Spain before La Liga was established in 1929, would go ahead as planned. Perhaps for the 46, or in spite of them, Barcelona would win their 9th regional cup, aided by their recovered 8.

5 months after crippling FC Barcelona, a newspaper reported that the flu had hit Atlético Madrid, on October 2nd:

“[The flu] has also angrily entered the sports world (which seems to be an ideal, outer world, superior to human miseries), and in less time than it takes to tell this, it has unfortunately decimated the football lines of Atlétic Club”

Unable to attend their next game, Atlético were fined 200 pesetas and docked 3 points.

King Alfonso XIII eventually recovered from his severe illness. 2 years later, upon noting the passion that football could inspire in the masses, he gave royal patronage to various football clubs, promoting Madrid FC to Real Madrid. In doing so, he cemented football as the national pastime of Spain, and the sport of the people.

Perhaps he, alongside the Spanish papers, both unwittingly responsible for the naming of the eponymous flu, saw football for what it is. When the Catalan journal, ‘L’Esquella de la Torratxa’, depicted the Roman God Mars and the Spanish flu using the earth as the ball in a game of ‘tragic football’, they intertwined their new reality with football in lasting metaphor. It just goes to show, football has never been an ideal, outer world, nor is it superior to human miseries. It is, and always has been, a microcosm for larger life.

– – –

UK

As men left to fight a war abroad, women in the UK were facing a new reality of their own. With the nation lacking a workforce, the government was reluctantly required to employ women in unprecedented numbers; by January 1918, 5 million were in work, with 700,000 working in the dangerous munitions industry. As they enjoyed their newfound freedoms, and sought a break from aiding the war effort, they began to play football in their lunch breaks.

This lunchtime recreation was soon elevated by events occurring in the war hundreds of miles away, when one munitions worker and football player, Grace Sibbert, learned that her husband had been captured by German soldiers, and was being held in a POW camp. Their munitions shop decided to set up a football team, which could play games to raise money for charity. Needing opponents, they sparked a torrent of other women’s munitions teams, and these teams began to play amongst themselves. Soon realising the potential women’s football had, particularly in filling the gap left by the lack of men’s football, some teams in the North East of England set up the Munitionettes Cup. These games were well attended, and raised a significant amount of money for various charities. As such, whilst football had halted in England when men went to war, it was brought back before they had returned.

Dick, Kerr Ladies F.C.

Their daily munitions work, however, was extremely dangerous, and when the Spanish flu arrived, it was only made more so. The immediate advice given from the Regional Sanitary Authorities had been that ‘fresh air and cleanliness, both of person and place, are keystones of defence’. Munitions work often lacked both of these factors, and the workers themselves were essentially designated as key workers, a modern term but an apt one. Rules of isolation were not applied to them. In fact, Arthur Newsholme, a public health expert, was aware that a complete lockdown would be most effective in curbing the spread and was also aware that conditions were beyond unsafe for munitions workers, but he did not want to undermine the war effort by allowing them to remain home.

This impacted burgeoning women’s football, as seen in a Munitionettes game between Armstrong-Whitworth 58 and North-East Marine Works, held at St James’ Park. The Armstrong-Whitworth team had 9 players ill with the flu, so only 2 of the first team were able to appear. 6 women had to be selected from the crowd, but they still only had enough to play a 9-a-side game. The flu-stricken team lost 5-1.

In this way, women’s football in the UK was borne of conflict, persisted despite complications, and even began to flourish. In the 1918/19 cup, the Blyth Spartans won in front of 22,000 people, with Bella Reay scoring an unbelievable 133 goals in 30 games of an unbeaten season. One such match was attended by over 50,000 supporters. Just 2 years later, the FA would cruelly ban women from playing on various grounds in the UK, a ban upheld for 50 years. Who knows where women’s football could be today if not for this decision, which punished mainly those who had put their bodies on the line for the war effort?

The munitions industry also played a part in what may be the most well-known footballing Spanish flu death. Angus Douglas (1889-1918) was a Scot who had made over 140 appearances for Chelsea and Newcastle. Playing on the right wing, he was more prolific in assists than goals, and in this way, helped Chelsea back to the top flight in the 1911/12 season. He was sold to Newcastle in November 1913, and by all accounts was in excellent form. He was in the prime of his footballing career, the prime of his life, when war struck. He began to work as a shell machinist at the Elswick Ordnance Company, and the dangers of the industry were soon realised as he lost a finger to blood poisoning. He met Nancy Thompson, and in April 1918, they had a child named Betty Douglas. Their newfound happiness was short lived. By December, both Angus and Nancy had fallen ill with the Spanish flu, and were quarantined to separate rooms. On December 11th 1918, 10 days after first showing symptoms, Nancy died at the age of 25. 3 days later, Angus would also succumb. Betty was left an orphan at 8 months old.

Unfortunately, Angus Douglas was one of many from his generation who would die in their prime. Indeed, he was one of many footballers to die after aiding the war effort. Noting the passion that football inspired in their communities, the government made a concerted effort to lobby whole football teams to sign up. In doing so, they hoped to prompt the local community to also sign up in a wave of national sentiment. As such, whole football teams, a whole generation of players were lost. They were in their prime footballing years, the perfect age to join the military, but considering the cruel demographics of the Spanish flu, they were also the most susceptible: Jack Stanley Allan (Newcastle) and Thomas Allsopp (Leicester, Brighton, Luton, Norwich) both served and died after contracting the flu. William Mountford Williamson (Leicester, Stoke) contracted the flu at Hamelin POW camp, and died on 2nd August 1918.

Armistice Day, 11th November 1918, allowed those who survived to return to scenes of great joy, but also of great devastation. Some soldiers returned home only to find their families and community severely stricken by the flu, and there are accounts of funeral processions hearing the joyful ringing of armistice bells. Some soldiers returned home after surviving multiple years of war, only to die within weeks after contracting the flu. Other soldiers unwittingly carried it straight into their own homes, bringing devastation where there should have been great celebration. It is no wonder that we see reports in the UK of the flu triggering serious mental disorders, and a steep rise in suicides, prompted both by trauma and the uncertainty of the future. Ultimately, the Spanish flu would take at least 230,000 lives in the UK.

The end of war marked the gradual return of football to England. It began with small, regional competitions, with the league scheduled to return in September 1919. Little precaution against the flu was taken in the footballing world. Indeed, in the midst of the flu, fans were still attending in large numbers, with Chelsea recording 20,000 to 30,000 fans attending games, even as the area struggled to handle the sheer devastation that the flu wrought.

In Scotland, the league had not stopped for the war, and it certainly would not stop for the flu. This was reportedly a measure to increase morale. It may not have been an effective morale boosting measure for fans of Hibernian FC. Dan McMichael (1860-1919) was their manager, and also their treasurer, secretary and physiotherapist. He led them to the Scottish Cup in 1902, and they won the league the following year. 18 years after revitalising the club, however, they were bottom of the league. He was travelling back to his home following a 1-1 draw, but collapsed. He succumbed to the Spanish flu 5 days later. Like many victims, he was buried in an unmarked grave. In 2013, Hibernian supporters discovered the plot, and raised money for a gravestone. A ceremony was held, attended by 400 people.

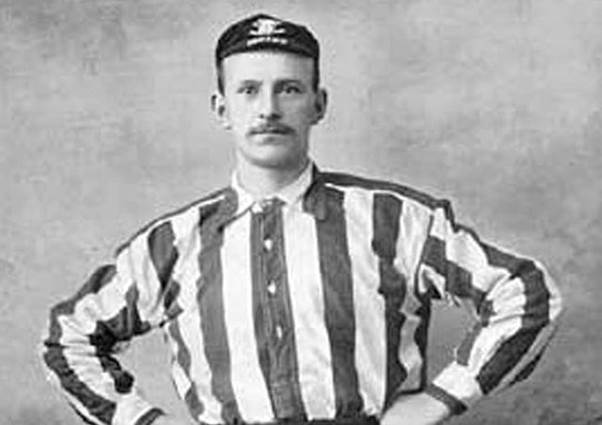

The Spanish flu also claimed the life of one of the best goalkeepers of the era, and a man with an incredible story.

The story of John Edward ‘Ned’ Doig (1866-1919) commenced with 3 wooden beams taken from a shipyard, fashioned into a goal frame, with which he would practise. His football career took shape in 1884, when he attended an Arbroath game, where the team was without a goalkeeper. As Ned’s brother recalled, someone in the crowd shouted ‘let Ned Doig play!’, and so it began. He remained on the team, and played his first official game for them on the 6th February 1886, aged 19 years and 3 months.

He was 5’6 and ambidextrous. He would train by tying a ball to the crossbar, and punching it with either hand with such force it would loop around twice. He could also kick the ball to a specific individual on the halfway line, a much-reported feat at the time. He had made his own dumbbells to keep either side of the goal, and would often use them to exercise with on the pitch. In both 1887 and 1888, he came first or second in 6 events at the Arbroath Sports Day. His party trick was buttoning up his jacket, standing in front of a chair, and jumping backwards over it, a skill his children recall he could still do at age 50.

In 1890, he joined Sunderland AFC. It started inauspiciously, not because of poor performance, but because it was discovered that he had not been correctly registered; Sunderland became the first club fined for this offence, and his first appearance for the club led to a 2-point deduction.

It could only get better from there, and indeed it did. As one of the central members of the ‘Team of all Talents’, Doig helped them to 4 titles. He quickly became a fan favourite, not only due to his skill, but also his remarkable personality. Immediately after joining, he began a run of 108 consecutive appearances, missing his first game for the club on January 6th 1894.

In 1896, Doig helped Scotland win against England for the first time in 7 years: ‘Scotland had won. Without the five Anglo-Scots – Doig, Brandon, Cowan, Bell and Hyslop she could not have done it. Let that forever be remembered.’ Doig was carried off the pitch on the shoulders of fans.

As they carried him away, he had a wonderful exchange with a fan from his hometown:

One fan from Arbroath shouted: ‘Give me a lock of your hair, Ned, to take home to Arbroath’

Doig replied: ‘I’m awful sorry I cannot oblige, friend, but you can take my best wishes to them at home’.

It should be noted that Ned Doig was bald.

In fact, Ned Doig was famously bald, and incredibly sensitive about the fact. He would wear a cap at all times, and fixed it beneath his chin with an elastic strap in order to avoid losing it. He would, however, lose it twice in his career, a fact remembered because both times, Doig chased after the hat instead of the ball, completely ignoring the game.

Prying his hat from him might thus have been a good tactic for an opponent, but only if you could survive his notorious temper. In 1899, in a game against West Brom, Doig dived to clear the ball and opposing player Bassett sat on his head. Later in the game, having bided his time, Doig punched Bassett to the floor, and sat on his head in retaliation. His teammates were not immune to his temper. It was a custom for players to get a half bottle of wine on away days, and Doig would always keep his in his bag to share with his wife on Sundays. One day, 2 of his teammates took his bottle, drank it, and replaced it with water. The following day, Doig came to the training ground with a carving knife and had to be restrained by the trainer.

By 1904, Doig had spent 14 years with Sunderland, a record at the time. He had played 417 games, and missed only 13. Across the season, their average goals conceded were 37.4, compared with 51.6 for the other teams across those 14 years. He is still fondly remembered by Sunderland fans, for obvious reasons, as one of the best players in their history.

Thomas M. M. Hemy’s ‘Sunderland v. Aston Villa 1895’ is one of the world’s first football paintings. It depicts a match between two of the most successful English teams of the time. It was held at Newcastle Road, and the game finished 2-2. It is currently exhibited at Sunderland’s Stadium of Light. Ned Doig is in goal.

His relationship with the Sunderland board, however, soured. Doig chose to move to Liverpool FC, who had recently been relegated to the second division. On Saturday 22nd April 1905, in front of 28,000 fans, Liverpool would win 4-0 against Manchester United to clinch promotion back to the top flight. All the players were carried off on the shoulders of fans, and Liverpool returned to the first division. This is likely the final highlight of Doig’s career.

He began to suffer from rheumatism, lost his place in the team, and never recovered his starting spot. It is around this time that an unknown writer penned the following poem:

There’s life in the old dog (Doig) yet.

Not long ago ’twas given out the veteran Doig was done

and strange reports were going about of the baldy-headed one.

‘Twas said he’d joined a fighting band and O’Brien clean knocked out

and thus received the damaged hand thro’ giving him a clout.

Therefore it’s pleasing to the mind and helpful to the soul

to know that actions of this kind don’t come under Teddy’s role.

The lines below prove once for all that Scotland’s famous son

is still as active with the ball as many a younger one.

He may have given a “bob” or two to whoever these lines sent

but this he’ll easily renew by getting this week’s rent.

His last game for Liverpool was on the 25th April 1908, aged 41 years and 165 days, and he remains the oldest player to have played for the club. A week later, he received a postcard through the door. It was from Liverpool FC, and stated ‘your services are no longer required’. According to his children, upon receiving this postcard, he trashed their kitchen.

After a few more seasons in the Lancashire league, he retired in 1910. His career had spanned 25 seasons, and he played at least 1055 games of football. Of his games in the top flight, he had kept a clean sheet in 30% of them.

Doig was only able to enjoy his post-football life for a few years before war broke out. 3 of his 8 children left to serve. Though all 3 survived, one eventually deserted and hid in their house in order to avoid the Military Police.

In his long career, Doig had only missed a handful of games through illness. Around the 1st November 1919, he contracted the Spanish flu, and was taken to a Liverpool hospital. By the 7th of November, Ned Doig had passed away. He was buried in Anfield Cemetery.

The Sunderland Echo reports: ‘His widow, Davina, was later to say that he died of a broken heart from seeing all the boys returning from the ravages of the World War, with little prospects for the future’.

All Ned Doig’s boys, and the rest of the men and women who dedicated their youth to their nation, got in return for their plight was the title of ‘the Lost Generation’.

– – –

URUGUAY

It was arriving Europeans who spread the flu in South America. In Sao Paulo, however, the first cases were amateur footballers from Rio, who were taken ill in October 1918. More cases soon emerged in the Hotel D’Oeste where they had been staying, and it quickly began to spread further. Across the region, most deaths occurred in Brazil and Argentina, with the latter having at least 15,000 deaths. Using the open-air rule, South American football largely continued.

In Uruguay, Nacional had been dominant for years on end. In 1917, they won the league and were Copa de Honor champions for the 5th year straight. In the previous 18 years, they had won 6 league titles and 7 Copa de Honor titles. Of great importance to their sustained success was much-loved club captain Abdón Porte, a defender who had played over 200 games for them.

The 1918/19 season was not a natural continuation of their dominance, and the flu made a difficult season even worse.

Even before the season had begun, a tough decision was made. It was determined that Porte was no longer performing well enough to start for the club, and his role was to be reduced.

No longer a defensive stalwart, he managed to start a game against Charley FC, on the 4th March 1918. They won 3-1, and by all accounts, Porte played well. Team celebrations began as usual, with executives and players meeting at the club headquarters.

Porte left the gathering at 1am. Alone, he took a tram to Nacional’s stadium, the Estadio Gran Parque Central. Standing in the centre of the pitch, where he had celebrated with the team and their fans many times over, Porte shot himself. A dog found his body, and with it, two letters. One was to his family, and the other was to the club president. The latter read:

“Dear Doctor José María Delgado: I ask you and other members of the committee to take care of my family and my dear mother, as I did. Goodbye, dear friend of life”

The club, the country, and the footballing community were shaken. To this day, Porte is remembered in Uruguay, particularly in the club he couldn’t bear to leave. A Nacional executive said:

“Nacional was Porte’s ideal, he loved the club like a believer loves his faith, like a patriot loves his flag”.

Just a few months later, Montevideo was hit hard by the Spanish flu. In the league and in the cup, Nacional were facing their most difficult challengers in years, fighting a close battle with Peñarol.

A game was to be played between the two for the Copa de Honor, on the 1st November 1918. The day before, however, it was reported:

‘Apparently the “flu” is a great enemy of Nacional. First, some players, then others, later the fans and finally the rest of the players and even the president and the same delegate, Mr. Rodolfo E. Bermúdez have been attacked by the annoying ailment. We wish all of you a speedy and frank improvement.’

Peñarol refused to postpone the match. Though several of their own players had been ‘decimated by the disease’, they appeared with a team built of backup players, knowing Nacional could not attend at all. Peñarol won the Cup without kicking the ball. Later, they would also win the league.

In 1918, Nacional lost everything, most importantly their great captain.

– – –

PARAGUAY

In Paraguay, the flu contributed to an extraordinary playoff series.

In the Primera División, after all games had been played, Cerro Porteño and Nacional were level on 21 points. At the time, they also each had 2 league titles. After some deliberation, it was concluded that they would play a deciding game, with replays if necessary.

A tense game was predicted, and scheduled for November 10th 1918. Nacional were up 2-1 in the 105th minute. As they returned to the pitch for the second half of extra time, the electricity went out. Attempts to fix it were fruitless, and it was decided that the final 15 minutes of the game would be played in the coming days.

It was in these few days that the Spanish flu hit Paraguay.

It was only 3 months later that authorities allowed the final 15 minutes to be played. On January 12th 1919, to Nacional’s dismay, in the small window that they had, Lázaro Avila scored again for Cerro Porteño. The match ended 2-2. Fans and players would have to wait longer, another game was required.

The first replay also ended in a draw. The two teams were clearly perfectly matched, but one was about to attain its enduring reputation.

The second replay began. By the 70th minute, Nacional were 2-0 up. To this day, Cerro Porteño are affectionately called ‘El Ciclón’ (The Cyclone), a name that some believe stems from this game. It is no wonder why. In under 10 minutes, they managed to score 4 goals. Watching fans saw their team harness the wind itself, and perhaps that was the only element that could differentiate between these two teams.

Cerro Porteño in 1913

After 300 minutes, 4 matchdays, almost 4 months, 12 goals, and after the intervention of electricity, plague, and air, Cerro Porteño finally won their third title in club history.

Clearly, football in this time was not a sport for the impatient.

– – –

A century from now, what will be remembered of football during the coronavirus pandemic? Perhaps, much more so than in 1918, it will be the panic of would-be victors at the potential of a ‘null and void’ season. Perhaps it will be the despair of fans at the prospect of an extended period with no football at all. Or perhaps, it will be the silence of the stadiums, and the realisation that it truly is the fans who make the game.

What is and was certainly true, both now and then, is that in a world gone mad, football provides much needed morale; what we need more than anything are those stories of persistence, of heartbreaks and miracles, and the knowledge that no matter what, there’s always another match to be played.