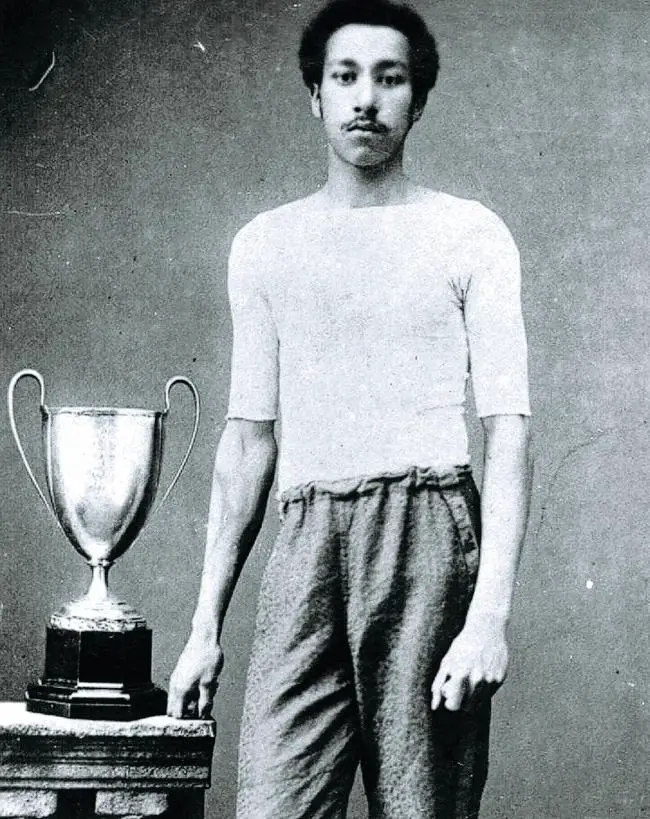

In an interview from 1888, Arthur Wharton recalled overhearing a conversation between two fellow track competitors some years before. “Who’s he,” one rhetorically asked, glancing at Wharton, “that we should be frightened of him beating us? We can beat a booming n***** any time.” Wharton approached the men and coolly asked if they wanted to box. They wanted no part of him.

In those days, it is unlikely that either of those racists could beat Wharton in an athletic competition of any kind. He was one of the fastest men alive, the first on record to run one hundred yards in under ten seconds. Not long after, now on a bicycle, Wharton beat the record for the shortest traveling time between Preston and Blackburn (16km/10mi). Seemingly gifted at everything he tried, Wharton turned to football.

As an adult, Wharton grew a thick mustache that extended most of the way across his narrow face. He wore a short afro, sometimes with a side part. In the few photos that exist, his expression is serious, but not stern.

Wharton began his career playing for then-amateur Darlington, before joining regional powerhouse Preston North End. He later earned a professional contract with Rotherham Town. A short, unsuccessful stint at Sheffield United in 1894 was Wharton’s last stop at a major club, though he played and briefly coached (notably coaching a young Herbert Chapman with Stalybridge Rovers) for several more years.

By signing that contract at Rotherham Town, Wharton, a keeper, and occasional winger, became the first Black professional football player in England. With the game’s institutions and norms still very much in an early development phase, there was not the quality gap between amateur and professional we see now. Still, himself following in the footsteps of a string of Black amateur footballers, Wharton marked a shift, as the first in a long line of Black stars in English professional football.

Counterintuitively, then, Wharton was all but lost to history for almost a century after his retirement. Those who had seen and known him died, his groundbreaking career never fully appreciated. Phil Vasili is primarily to thank for Wharton’s reemergence in the public eye. Vasili’s research into the history of Black players in the English game is responsible for much of the biographical information included in this piece.

The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis has forced much of the world to reflect on the telling of history and to question which figures from the past are really worthy of celebration. Statues commemorating confederate generals and slave traders have been pulled down, either formally by governments, or by people who have grown tired of waiting. Not enough energy, perhaps, has been spent thinking about the issue of memory in reverse. Some figures from the past deserve more attention, in part because their lives help frame and inform the present.

Arthur Wharton’s is a story worth telling, not because of his greatness and uniqueness – though he was great and unique — but because it offers such insight into the time and place in which he lived, a period both similar and different from our own. His life is a story about racism and Social Darwinism, about class and general strikes. It is a story about a pacey and stylish keeper. Wharton lived a football life, in the all-encompassing cultural and societal sense of the phrase.

Wharton was born in Accra, Ghana, then the British Gold Coast, in 1865. His father was a preacher in the Wesleyan Methodist Church, known in Ghana as the Standard Wesleyan Church, at that time a relatively new Protestant movement. As an adolescent, Wharton planned to follow his father into the Church, with a particular interest in becoming a missionary. His mother came from a royal line of the Fante, a prominent people in Ghana and the Ivory Coast. In Wharton’s time, the Fante had a complicated relationship with the British. They shared a common enemy in the Ashanti people, another ethnic and political group in the region. But Britain was also widely responsible for the dissolution of the Fante Confederacy in 1873, a mostly autonomous governing body that the empire had supported the creation of only five years prior.

Unlike most Ghanaians under British rule, Wharton’s royal blood granted him privilege through his youth. Yet he came of age in the early years of what would become decades of intense pushback against colonial rule. For safety, his family sent him to complete his education in England. Now on his own in a new culture, Wharton decided a career and life in the Church was not for him. He had fallen in love with sports.

Reading analysis from Wharton’s contemporaries, he sounds like the type of keeper to make the daring Bayern Munich and Germany goalie Manuel Neuer look conservative and risk-averse. To be fair to Neuer, Wharton was playing a different game. Keepers were at that time allowed to pick-up the ball anywhere in their own half. This rule made goalkeeping easier, but also more complicated. With expanded scope, positioning was especially crucial. One could easily get caught out. Wharton’s (literally) world-class speed helped him make the position his own. He would tear across the pitch to break-up attacks, knowing that he could get back on his line quickly.

Aside from his speed, Wharton’s most noted attribute was his confidence and strength in punching the ball clear. English football of the 1880s was a physical game, even chaotic to the modern eye. Sometimes Wharton’s punches landed on heads. Those racist sprinters may have been wise to decline Wharton’s offer to box.

Wharton was an idiosyncratic player, too.

Reminiscing some years later, one Wednesday fan wrote: “In a match between Rotherham and Sheffield Wednesday at Olive Grove I saw Wharton jump, take hold of the crossbar, catch the ball between his legs, and cause three onrushing forwards – Billy Ingham, Clinks Mumford, and Micky Bennett – to fall into the net. I have never seen a similar save since and I have been watching football for over 50 years.”

I don’t even know where to begin with that, but it’s incredible. To be fair, this fan’s account cannot be corroborated, but if nothing else, Wharton deserves the benefit of the doubt. Nothing is gained from disbelief. Wharton also became known for crouching next to one of his goalposts and waiting for a shot to be taken to dive into position. It is almost as if the game was too easy. Given how few words Wharton was allowed to speak on his own behalf, it is hard to know what motivated his playing style. Regardless, in spite of any criticisms, he entertained and brought joy to fans, fulfilling the primary purpose of the game. It seems most teammates were similarly enthusiastic about Wharton’s talents and glad to have him as a teammate. As Arsene Wenger observed in a recent interview, on a certain level meritocracy overrides racism in sports. If you’re good, you’ll find a space for yourself in a team.

However, Wharton was loved and admired by fans, but in a peculiar way, as an objectified figure. Indeed, judgmental, racially informed critiques were often levied against Wharton from the press. One Preston-based journalist scorned: “Good judges say that if Wharton keeps goal for the North End in their English Cup Tie the odds will be lengthened against them. I am of the same opinion. Is this darkie’s pate too thick for it to dawn upon him that between the posts is no place for a skylark?”

As in all most phases of life, both in Wharton’s day and in ours, society draws sometimes unwritten lines in the sand that confine the behavior of racial minorities. Like certain physical borders around the world, white people can traverse social norms freely in a way people of color often can’t. A daring style could certainly be more easily permitted for a white player, whose intellect would not be so quickly doubted.

Admittedly, I approach Wharton’s story as an outsider. As an American, I make no claim to immersion or fluency in English football culture. After all, I associate the Premier League with early mornings and coffee (a 6:00AM pint would be a step too far in the name of authenticity, I think). Still, as a heavy consumer of the game and the media that surrounds it, I can’t believe I hadn’t heard Wharton’s name until recently.

Most of my surprise comes from the comparative fame of Jackie Robinson, the first African American player allowed into Major League Baseball.

Signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, Robinson was an instant star. He earned the Rookie of the Year award and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player two years later. Decades on, Robinson is a household name. Most kids meet him in picture books or history classes (though in some states, African American history appears so sparely in school that the curriculum ends up being flatly ahistorical). His number, 42, is retired in the MLB and is inscribed in some notable way in every ballpark. Perhaps more than his considerable abilities, Robinson is remembered for his temperament. Despite enduring horrible abuse from fans and sections of the media, he seldom reacted, knowing that he had to represent to America just how wrong racist stereotypes really were. Seventy years later with relatively minimal racial progress to show for it, one can understand why some protesters have grown impatient with this approach.

Though baseball has endured waning popularity in recent years (mostly due to its almost aggressive slowness), culturally the game means something similar to Americans as football does in England. It is not just a sport, but a pastime, a nostalgia, an essential piece of the national identity. In theory, then, Wharton’s cultural import and fame should match Robinson’s. Certainly, Americans today are just as racist as our former colonizers, if not more so. It takes far less than eight minutes and forty-six seconds to see that. So why is Robinson so present while Wharton has only a single major biography to his name?

As the near-global uprising in response to the murder of George Floyd demonstrates, in revolutions, timing is everything. Robinson’s first game for the Brooklyn Dodgers was in 1947, only seven years before Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the seminal Supreme Court case which desegregated schools on the grounds that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” This decision marked a reversal of the shameful Plessy v. Ferguson case from 1896. A year after Brown v. Board, Rosa Parks, an African American woman from Alabama, refused to give up her seat on a city bus for a white passenger. Her subsequent arrest ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the leadership of which contributed to the rising star of a young reverend — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. All of this is to say that Robinson was an agent of change, but he was also symptomatic of a rising tide. The first stages of legal integration were coming, and Robinson had a part to play, as equal parts man and symbol.

By comparison, Wharton was an outlier. Certainly, other Black players followed, notably Walter Tull, the Tottenham, and Northampton Town star killed fighting in World War I. But the societal change that Robinson signaled was nowhere to be found in Wharton’s time. The late Victorian era in Britain saw a widespread embrace of Social Darwinism. Actually a perversion of Darwin’s theory of evolution, the Social Darwinists believed in racial pseudoscience. They argued that each race had evolved with different abilities. Black people, it was understood, evolved into optimal workers, but certainly not thinkers or leaders. Anyone familiar with Nazi literature will recognize this type of language. Obviously, the science was nonsense, and willful nonsense at that. All it did was validate social and economic oppression that already existed.

Against this backdrop of unmoving intolerance, Wharton could not meaningfully change many hearts or minds. He moved to England in 1882, less than fifty years after the abolition of slavery in Britain. Fifty years is a long time in one sense and quite brief in another. Few Black people had been famous and even fewer had enjoyed the kind of fame athletes enjoy as the subjects of admiration. As an immigrant, the hill Wharton faced was even steeper. Confined by his time, he could not be seen as a meaningful step towards integration.

Ultimately, the stories Robinson and Wharton are useful for different reasons. Robinson’s story is heavily mythologized. He is perhaps less emblematic of America in the flesh than he is of who and what many Americans imagine themselves to be. Wharton does not so easily fit into a teleological narrative because he shows what Britain was, and to some extent still is.

Pseudoscientific, racist attitudes contributed to the public’s view of Wharton on the field, too. The keeper was constantly noted for his (admittedly world-class) speed. Seldom, though, was credit given for the intellect that must have been required for his playing style to work. Without incredible positional and special sense, even the quickest goalie would get exposed constantly). Manuel Neuer is perpetually lauded for the intellect his playing style demands. That type of analysis couldn’t be applied to Wharton because it didn’t match a broken worldview. In this way, Wharton’s sporting achievements were misunderstood. They were too often viewed as merely an accident of biology, the aftereffect of a people evolved to do physical labor for superior races.

Perhaps this kind of objectification explains why Wharton faded into obscurity the moment he lost a step on the field. The game forgot about him because it had never known how to appreciate him in the first place. Little is known about his life away from football. The next and last fifteen years of Wharton’s life were spent working various jobs, mostly in the mining industry.

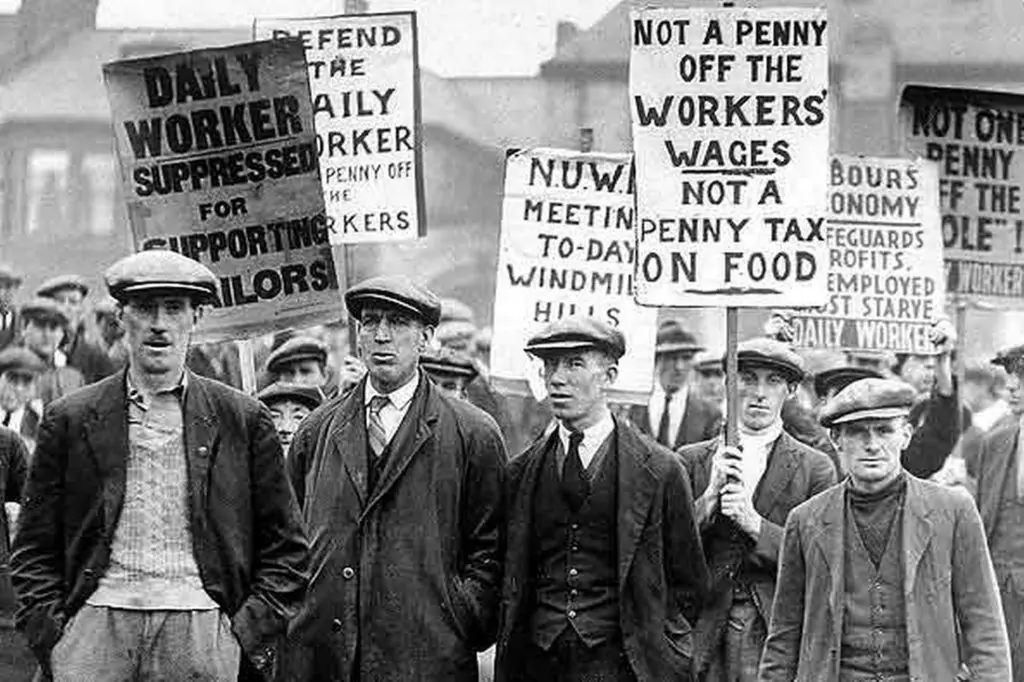

Wharton participated in the famous General Strike of 1926 and refused to cross picket lines, even while he desperately needed the money. Coal miners had been locked out of the mines following their refusal to accept a 13% pay cut and an extra hour of daily work. Even in times of economic hardship as British industry struggled in the post-World War I economy, these terms offered by the mine owners were ludicrous given the essential and dangerous nature of the job (today’s football fans should be familiar with the question of whether employees or owners should shoulder financial burdens, but of course the comparisons only go so far).

The government was somewhere between unable and unwilling to negotiate a deal. On May 3rd, the Trades Union Congress called a general strike. Other industries joined in solidarity. The economy abruptly shut down. As folklorist Rachelle Hope Saltzman writes, “few have noted that the British world was temporarily turned upside down during the General Strike.” After a chaotic nine days, the strikers lost their battle with industry leaders. Most returned to the mines with emptier pockets. Many were replaced and their jobs permanently.

Decades and thousands of miles removed from his royal roots, it is interesting that Wharton embraced a kind of working-class solidarity. Perhaps down in the mines among the minimally paid, coughing miners, he something of himself, or rather of the oppression he faced, just in a different form and for different reasons.

This sort of attitude is consistent with what else is known about Wharton. He often participated in charity games, even while not being much better off than those the money raised was destined for. During the first World War, too, Wharton volunteered for the Home Guard, ready to defend Britain in the event of an invasion (the Guard didn’t have to properly kick into action until World War II). It was an unpaid position and might well have become an unpaid sacrifice. Wharton should be remembered for what he did and represents, but also for who he was.

Through these post-football years, it seems Wharton struggled with alcoholism and a difficult relationship with his wife, Emma. He died in 1930 at sixty-five, sick and all but penniless. After a well-attended service, no headstone was left to mark his grave. Little was written about Wharton for decades. Generations of Wharton’s knew little to nothing of their trailblazing ancestor.

For all the ability and personality Wharton contributed to the England of yesteryear, his presence can and should be larger now than ever. Rather than Jackie Robinson, Wharton’s delayed impact can be more reminiscent of another African American icon, “Blind” Willie Johnson, the early twentieth-century singer, and guitarist. The son of a sharecropper who lost his eyesight as a child when his stepmother threw lye in his eyes, Johnson was never fully appreciated in his time. He died poor after being refused entry at a hospital, most likely due to his race. Years later, his music gained great acclaim, with artists like Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton covering his songs. Johnson’s sound was recognized as distinctive and influential, his name given a proper place in music history. In 1977, NASA included Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” in a compilation programmed into the Voyager probe. Should the craft ever come into contact with life yet unknown, Johnson’s story of poverty and loneliness will tell them part of our story. The Voyager is now somewhere out in the dark, cold expanses beyond the solar system.

While he’ll probably never be as interstellar as Blind Willie Johnson, Arthur Wharton can have a second life with us in the present. We just have to remember.

There is intrinsic value in studying people from the past, particularly those whose contributions went largely unrecognized. The act of remembering makes us more human. It helps us to see who we are, for better or worse.

History is also a resource, chock-full of lessons, and context. Wharton’s story, for instance, lends credence to Raheem Sterling’s recent quote: “I feel like I speak for most Black people – everyone is tired.” Indeed, speaking to one source of fatigue, in particular, the racism Sterling has faced in the press is a clear descendent of that endured by Wharton. Extra criticism, sometimes having nothing to do with football, is applied more easily to Black players. Accusations of laziness and bad attitudes are seldom aimed at white players but often work as an easy stereotype when analyzing an underperforming Black player. There is nothing new under the sun.

The inequality of Wharton’s time remains today, too. As Marcus Rashford has powerfully noted in his successful campaign to extend school meal programs for underprivileged kids, the burden of hunger does not fall evenly. “In England today, 45% of children in Black and minority ethnic groups are now in poverty. This is England in 2020…” Successful Black players like Rashford may be rich these days, but the economic conditions that killed Wharton have not changed enough for people of color.

Players in the NFL and NBA have been especially vocal criticizing team owners and league officials for profiting off the talent of Black players while showing little interest in promoting racial equality. Football is no different. Wharton’s experience in the Football League shows how exploitation and objectification go hand in hand.

While expressing pain, Trent Alexander-Arnold wrote of the promise the Black Lives Matter movement offers to our times: “But I also have hope. Hope that the world is awake at this moment. Finally willing to learn. So while we have this opportunity, where people are listening – let’s speak, educate, campaign, and let’s promote the message that better education brings change.” Black players have a voice like never before. The rest of us have a renewed chance to listen, hopefully honoring Wharton’s legacy and offering some kind of posthumous apology in the process.

Arthur Wharton was a man and player of his time, but he can still live with us in ours. Perhaps Wharton’s status as the first Black professional footballer in England is more semantic than qualitative, but that is not the important part of the story. Remembering his life, his Black life, is what matters.

“He (Arthur) ended his days sadly, but he was not a sad figure, he did things his own way, despite obstacles put in his way.” – Phil Vasili