When Red Bull tried to set foot into German football for the first time, they initially tried to use the same method they had success with elsewhere: Take over an existing, possibly struggling team and transform them to their expectations, like they had done with Austria Salzburg or the New York MetroStars. Even back then, their first choice was FC Sachsen Leipzig, although there were several other clubs on their radar. After fans protested and negotiations with 1860 Munich, FC St. Pauli and Fortuna Düsseldorf were equally unsuccessful, they turned back to their initial pick Leipzig and started their own club. So – why exactly Leipzig?

To understand this, we have to look at Leipzig’s football clubs and the city itself. Leipzig is the eighth-largest city in Germany, and (excluding Berlin) the largest one in the former GDR. Their population is bigger than Liverpool, Lyon, Genoa or Malaga. All those cities have established clubs, sometimes even multiple within the top division. At the time of RBL’s conception, the top club of the city of Leipzig meanwhile was just relegated to the fifth division. The only city with a similar size and situation was Essen, with Rot-Weiss sitting in the fourth division. Still, right in the center of the picturesque Rhein-Ruhr area, Essen was surrounded by successful clubs who could fill any desires for top-class football. Leipzig wasn’t. The closest city of similar size is Dresden, but their top club Dynamo also only played in the third division. The same was true for other clubs nearby like Jena, Erfurt or Aue. Cottbus, already quite a bit away from Leipzig just got relegated to the 2. Bundesliga, and while the drive to Berlin to watch a Hertha match only takes around two hours thanks to those lovely post-reunification East German Autobahn, it’s still quite a bit away for European standards. Other cities like Nuremberg or Wolfsburg weren’t closer either.

Given these circumstances, it’s no surprise that Red Bull saw Leipzig as their prime location to start a new, fresh club in Germany. Although this begs the question: Why not Dresden? Both cities have almost equal population numbers, sit in a similar geographic location not too far away from each other and have virtually no access to professional top-class football. Sure, Leipzig was a bit closer to other major cities, but gaining followers from outside the city and its surrounding areas wasn’t really the plan to begin with, at least for now.

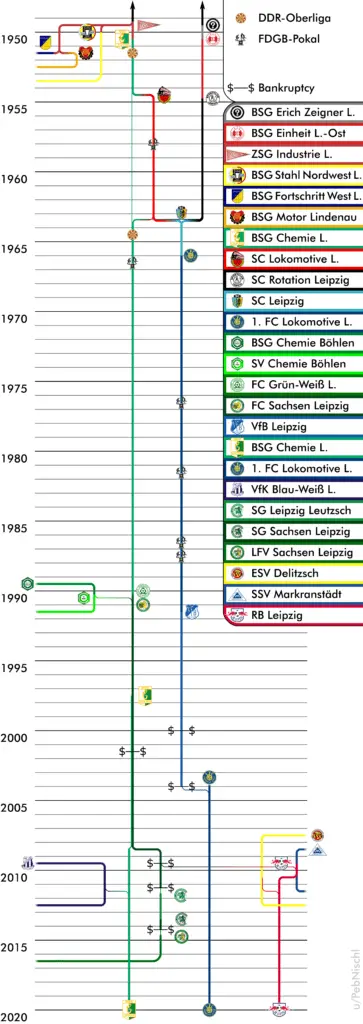

A major reason for Red Bull’s decision to pursue Leipzig from the beginning and not even really think about Dresden was the lack of competition. Even though Dynamo Dresden spent their time in lower leagues, the city and its fans still stood fairly unified behind the club. Establishing a competitor and convincing fans to join their new product would be hard. In Leipzig however, there was no other club with a unified fan base. All that was left of the long-gone glory days were two clubs, shadows of their former selves, who hated each other. This leads to the final why: Why was there such a power vacuum for Red Bull to push into? To understand this, we have to take a very long look back, all the way back to the end of WWII, and work through the history of post-war football within the city. Below is a simple and easy to understand diagram to help you tag along.

Pre-1949 – Under Soviet occupation, all pre-war clubs were outlawed. To replace them, new sport groups were formed all around the country. In the early years, those were often short-lived and frequently merged, split up and disbanded, sometimes even within weeks. Up until 1949, there was no nationwide football league, either. Combined with the fact that those clubs often had very similar names, usually SG City–District, everything earlier becomes increasingly hard to research. For the history of Leipzig football, we’ll focus on two of these SG’s:

SG Leipzig-Leutzsch played at the Georg-Schwarz-Sportpark in the district of Leutzsch, former home of pre-war TuRa Leipzig. TuRa was founded in 1932 as a workers team for a slot machine factory.

SG Leipzig-Probstheida meanwhile was based in Leipzig-Probstheida (who’da thunk it) at the Bruno-Plache-Stadion. They could trace back their roots to VfB Leipzig, the first German champions and the most successful club in the pre-WWI era.

Even back then, tradition was already an important part of fan culture. When TuRa and VfB faced each other in 1935, a newspaper wrote: “The game wasn’t on for long until you could sense the frantic, provoked emotions in both rivals stands, which was better described as hostility rather than competitive spirit”. As you can see, even back then no one liked the corporate shills.

1949/50 – The foundation of the first nationwide league brought more major changes with it. SG Leipzig-Leutzsch finished third in the Saxonian championship the year prior and therefore qualified for the new nationwide Oberliga. Before the season started however, SG Leipzig-Leutzsch merged with more than a dozen other clubs to form ZSG Industrie Leipzig. This is where the left branch of the diagram starts. Not even two weeks after its foundation, on the 1st April, 1949, ZSG Industrie already split up again into three distinct divisions. ZSG Industrie Leutzsch was renamed again shortly after to BSG Stahl Nordwest Leipzig and today exists as SV Leipzig-Nordwest in 10th tier. ZSG Industrie Hafen split up again in 1951, creating the new teams BSG Fortschritt West and BSG Motor Lindenau. Those two clubs merged back together after reunification and now operate as SpVgg 1899 Leipzig in the 9th division. The spot in the top division meanwhile stayed with ZSG Industrie Leipzig, where they finished in 8th.

Over in Probstheida, SG Leipzig-Probstheida was meanwhile renamed to BSG Erich Zeigner Leipzig, after some communist, as it was en vouge at the time. They missed qualification for the initial season of the Oberliga and thus played another year in the Saxonian league for the 1949/50-season, before qualifying for the newly founded second division, the DDR-Liga. This is the beginning of the right branch on the diagram.

1950/51 – Only a year later, the East German sports landscape was heavily reformed, as if all the changes prior hadn’t been confusing enough. To conform to socialist ideology, clubs were urged to turn into so called Betriebssportgemeinschaften (workers sport groups), BSGs for short. Every club was to be linked to a specific factory or organization, where players were employed as workers and excused for training or matches. Clubs who didn’t comply were seen as bourgeois and faced various kinds of repercussions, so by the mid-50s, virtually all clubs in the GDR were those worker clubs. The club name of those BSGs was determined by the branch of industry they were associated with. Police clubs were named Dynamo, workers clubs in the construction industry were called Aufbau, and so on. This is the reason why there are still loads of Dynamo or Dinamo clubs around, as they all were former police teams. Dresden, Zagreb, Kiev, Bucharest, Moscow, Houston (I’m not absolutely sure about them), and so on. ZSG Industrie Leipzig meanwhile was assigned to the local chemical plants and thus renamed to BSG Chemie Leipzig, which translates to BSG Chemistry Leipzig (They weren’t always too creative). BSG Erich Zeigner was meanwhile turned into BSG Einheit Ost Leipzig, associated to insurances and administrative institutions.

In the 1950/51-season, Chemie won their first championship. After finishing equal on points with BSG Turbine Erfurt, Leipzig won the final play-off match 2:0 in front of 60,000 spectators in Chemnitz. Einheit Ost meanwhile finished third in the southern division of the DDR-Liga.

1954 – While Einheit Ost finally got promoted to the top-tier Oberliga in 1953, Chemie came close to more silverware when they finished third in 1952 and second in 1954, before the East German sports landscape was again subjected to major changes. Unlike before, where bigger clubs of the same associated industry were spread all across the country, the new model provided for only a few major clubs per branch of trade, with all others only focusing on amateur sports. Leipzig got two of those so called Sportclubs, SCs for short. Einheit Ost got transformed into SC Rotation Leipzig, one of two SCs for the national print and publishing industry. The players of Chemie meanwhile were presented with two options: Either stay within the city and join SC Lokomotive Leipzig, the new club for the national railway services; or move to nearby Halle, where the SC for the chemical industry was located. Almost all players chose the first option, and while the remnants of Chemie Leipzig were downgraded to an amateur team in the fifth division, Lok took over their spot in the Oberliga and moved to the Stadion des Friedens in Leipzig-Gohlis.

The following years were marked by fights about the top spot in the city. While Lok initially struggled to reproduce Chemie’s results, fan interest was enormous. Derbys were moved to the much bigger Zentralstadion, where in 1956, 100,000 people saw the 2:1 victory of Lok over Rotation. To this day, this is a record for most spectators at a national league match in Germany. In 1957, Lok also won the East German cup, the FDGB-Pokal for the first time, and reached the final a year later. Rotation wasn’t as successful, usually finishing in the lower half of the table and never reaching the quarter-finals in the cup.

1963 – As decision makers in GDR liked restructuring things almost as much as building walls, the colour red and naming things after dead communists, more restructuring followed in the mid-60s. Officials now decided that one SC per district should be enough, regardless of the branch of industry currently associated with them. Therefore, in 1963, Rotation and Lok joined forces and merged into SC Leipzig. While the top players of both teams were signed by the new club, there was still a whole team worth of players and, more importantly, another spot in the league up for grabs. The solution was to resurrect BSG Chemie Leipzig and transfer all the leftover players, staff and the remaining Oberliga-spot to them. The amateur team, which had kept the name alive for the past years, was meanwhile integrated into the club as the new third team.

While SC Leipzig was seen as a prime contender for the championship, Chemie on the other hand was everyone’s first choice as a relegation candidate. After all, they were basically made up of inferior players from a partially successful team and one that had been mediocre at best. Nevertheless, in one of the biggest upsets in the history of GDR football, Chemie and the so called “rest of Leipzig” immediately won the league, three points ahead of SC Leipzig, who finished third. This was the last time a BSG won the title against the better funded SC-clubs. This was also the start of many animosities between the two clubs and their successors.

1966 – Not even three and a half years after conception, SC Leipzig was history again. (Did I mention that people liked to change stuff every few years?) The football sections of the SCs were separated from the main clubs and now formed independent football clubs. In Leipzig, this club was again assigned to the national railway services, and thus got the new name 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig. Unlike SC Lokomotive of the 50s, this club was however based at the Bruno-Plache-Stadion in Probstheida, former home of SC Rotation. The club also made its first international headlines, beating Benfica with star player Eusebio in the third round of the 1966–67 Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. While they were one of the top teams in the country for most of the 60s, Lok failed to win any titles before a surprise relegation in 1969. Meanwhile, Chemie won the FDGB-Cup in 1966, but started to struggle in the league. At this point, I’d like to take a moment to remember the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. Conceptualized as a tournament to promote trade fairs, only the cities with the biggest and most important ones competed in the early years. Over time, this definition slowly changed to “If you have a large parking lot in your town to hold a flea market, you’re in”, leading to clubs like ÍA Akranes and US Rumelange competing for the win (and subsequently losing by double digits in the first round).

70s – After Lok bounced back to the Oberliga immediately, they initially failed to gain traction, with their best results of the decade being fourth places in 1973, 1976 and 1978. Their cup campaign was more successful, however. After reaching the final in 1970 and 1973, they finally won the trophy in 1976 after a decisive 3:0 victory over FC Vorwärts Frankfurt/Oder. They also had an admirable run in the 1974 UEFA Cup, reaching the semi finals before being eliminated by Tottenham.

Spurs’ Martin Chivers scores against Lok Leipzig in the second leg at White Hart Lane

Chemie on the other hand couldn’t keep up with the better funded competition and thus became a yo-yo club, being relegated to the DDR-Liga thrice within just ten years.

80s – While Chemie continued their life yo-yoing between the leagues and spending more and more time in the second division, Lok now attacked in the Oberliga as well. GDR football in the 80s was dominated by Dynamo Berlin, a team with links to the Stasi, the national secret police. Said subtle links included the honorary president of the Club, a guy called Erich Mielke, being also the president of the Stasi. Dynamo Berlin was also often accused of receiving preferred treatment from referees and officials alike. They were pretty much the Bayern Munich of 80s East German football, with the important difference that the board of Dynamo supported the GDR being an unjust regime that killed people, while the board of Bayern supports Qatar being an unjust regime that kills people.

On matchday 18 of the 1985/86 season, the club from the capital played in Probstheida. While Berlin led the table, Leipzig, sitting in fourth place, needed a win to keep up any realistic chances of winning the league. Lok scored early and held on to the lead until the fourth minute of stoppage time, when referee Bernd Stumpf awarded a penalty to Berlin after a seemingly harmless foul. The decision was questionable and even TV images couldn’t resolve the situation. This lead to a massive outcry never seen before in East German football, with players and even party officials from Leipzig accusing Dynamo of match-fixing. To ease the pressure, Stumpf was banned for life from refereeing, and the fact that Lok finished the season only two points behind Dynamo fanned the flames even more. Only years later, in 2000, new footage of the incident was found, proving Stumpf’s decision to be indeed correct. In 1988, they again came second, this time only losing out because of goal difference.

Just as in the 70s, their various cup engagements were more successful. They won the FDGB-Pokal three more times in 1981, 1986 and 1987, and also proved their worth on the international stage. In the 1981/82 Cup Winner’s Cup, they reached the quarter finals after being beaten by Barcelona, who would go on and win the tournament. They also beat Girondins Bordeaux and Werder Bremen in the 1983/84 UEFA Cup. This was back in the days when a victory against Bremen still was considered an accomplishment. Their biggest run however followed in the 1986/87 Cup Winner’s Cup. After victories over Glentoran Belfast, Rapid Vienna and FC Sion, they again faced Bordeaux in the semi final. After a 0:1 victory in France, 73,000 fans came to watch the second leg at the Zentralstadion. That’s the official number anyway, other sources estimate up to 120,000 spectators that day. Bordeaux scored early, but Leipzig withstood the pressure for the rest of the match. In the end, Lok won 6:5 on penalties, with goalkeeper René Müller scoring the decisive last goal. They lost the subsequent final 1:0 against Ajax, but received praise from opponents and press alike.

1989/90 – 9th November, 1989, would forever be ingrained in German and world history, as on this day, VfB Stuttgart won 3:0 against Bayern in the RO16 in the DFB-Pokal. Also on the same day, some kind of wall fell in Berlin, which apparently made it to local news or something.

German reunification brought even more major changes to East German football, which had been unusually stable for the last 25 years. Clubs all over the country couldn’t compete with western wages, and thus lost key players left, right and center. Lok was no exception, with players like Olaf Marschall or Uwe Zötsche leaving for western clubs after the season. Moreover, those teams now had to operate in a completely unfamiliar capitalist system. To combat those problems, Lok proposed an idea to their rivals Chemie: Under the traditional name VfB, a new and competitive team, representing the whole city was to be formed by merging both clubs together. Chemie, however, had other plans than to unite with their hated neighbor and ditch their heritage as a workers club for a new identity.

BSG Chemie Leipzig finished the 1989/90 season in second place of the DDR-Liga behind BSG Chemie Böhlen, thus missing out on promotion back to the top flight. It was already clear that the 1990/91-season would be the last of independent East German football, and while clubs from the Oberliga had good chances of at least qualifying for the 2. Bundesliga the season after, they would’ve had to win the DDR-Liga to even participate in the qualification tournament for the all-German second division. Meanwhile, Böhlen had just changed their name from BSG Chemie to SV Chemie to signify their changed identity and rid themselves of the now unpopular East German baggage. They also were in financial troubles, so Leipzig made them an offer: A merger of SV Chemie Böhlen and BSG Chemie Leipzig, who had also just changed their name to FC Grün-Weiß Leipzig after the season. They also got themselves logo with a frog that’s also a football, which isn’t really important to the story, but just look at it. It’s a football frog.

Back to the story. Böhlen accepted the offer for a merger, which in reality was more of a takeover to get Chemie, sorry, FC Grün-Weiß Leipzig their Oberliga-license. Sadly, this also meant that the frog was gone already after just two months, with the new club now called FC Sachsen Leipzig.

1990/91 – The final season of GDR football was all about qualification for the new unified German leagues. Like many things, stuff that was abundant in the west was very scarce and contested in the east, so only two spots for the Bundesliga were available. Those were claimed by Hansa Rostock and Dynamo Dresden. Meanwhile, Lok only finished seventh, while Sachsen barely clinched the final 12th spot that guaranteed participation in the qualification tournament for the 2. Bundesliga. While Lok cruised through their group and won one of the last two spots in the second division, Sachsen finished dead last and was seeded in the new third division, the Oberliga Nordost.

1991/92 – For their first season in unified Germany, 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig also tried to reform their identity, because you know, they hadn’t done so since the 60s. They took up the idea from 1990 and named themselves VfB Leipzig, after the first German champions that had played in Probstheida. This was somewhat ironic, since their home ground wasn’t deemed suitable for playing, so the club had to leave Probstheida for the Zentralstadion during the season. After injuries to key players like Damian Halata and Ronald Kreer, VfB Leipzig only barely avoided relegation. They also signed expensive players like former French national Didier Six, which put further strain on their already tight budget. Sachsen meanwhile finished fifth in the Oberliga Nordost, a full 19 points behind winners Zwickau (and remember, this was back in the days where a win only got you two points).

1992/93 – While the 1991/92 season of the 2. Bundesliga was played in a northern and southern division, this following year was planned as a single goliath-league with 24 teams. Still, VfB Leipzig almost didn’t participate after being short on 1 Mio. D-Mark in order to get their license. After a successful appeal, they surprised many by becoming one of the league’s best teams, even after setbacks like losing top scorer Bernd Hobsch to Werder Bremen in the winter break. More controversial was the announcement by coach Jürgen Sundermann to leave the club at the end of the season and join Waldhof Mannheim. Still, Leipzig kept up with the other clubs in the top group. While the Freiburger SC won the championship by a clear margin, a three-way battle developed behind them for the remaining two promotion spots between Leipzig, MSV Duisburg, and, of all teams, Waldhof Mannheim. With a win in Jena and a scoreless tie between Mannheim and Eintracht Braunschweig, Leipzig inherited third place before the final two matchdays. In the penultimate game of the season the opponents met each other face-to-face. After another scoreless tie and two red cards for Leipzig, the decision only fell on the final matchday, when Leipzig won 2:0 against FSV Mainz 05 and Mannheim lost 4:3 in Wuppertal, thus promoting VfB Leipzig to the Bundesliga.

In the meantime, Sachsen Leipzig won the southern division of the Oberliga Nordost, but still weren’t allowed to participate in the deciding qualification round for the 2. Bundesliga for financial reasons. They also won their first Sachsenpokal, the regional cup tournament for Saxony. Furthermore, their stadium in Leutzsch was renamed to Alfred-Kunze-Sportpark, to honor the coach who brought them the surprise championship in 1964. After all, they hadn’t renamed anything for almost two years now.

1993/94 – VfB Leipzig was faced with more troubles for their initial Bundesliga season. While key players leaving for richer clubs was a common occurrence by now, the Zentralstadion showed to be deeply unsuitable for them. With a maximum capacity of 50,000 spectators, only 8000 people per game were expected, not least because the surrounding area was traditionally Chemie/Sachsen territory. Also, spectacular transfers like Darko Pančev, who came from Internazionale, could not prevent immediate relegation back to the second division. With three wins, eleven draws and twenty losses in their only Bundesliga season, they currently sit in second-to-last position in the all-time Bundesliga table.

Sachsen Leipzig meanwhile finished fourth and qualified for the new Regionalliga Nordost, while winning another Sachsenpokal.

Late 90s – VfB Leipzig made numerous expensive transfers over the next years in order to achieve a rapid return to the top flight, all with questionable returns. Speaking of returns, they also returned to the Bruno-Plache-Stadion in Probstheida in 1996, when the safety issues there were finally properly fixed. After a draw on the final matchday against their direct relegation opponents from Wattenscheid, VfB Leipzig dropped to the third division in 1998, where they met up again with their city rivals FC Sachsen, who had won their third Sachsenpokal in the meantime. Following a second place finish in 1999, the financial problems for VfB Leipzig became so bad that insolvency was the only option. To make matters worse, they also failed to qualify for the next season in the Regionalliga, which was to be slimmed down from four divisions to just two. Sachsen Leipzig initially made the cut for the 2000/01 Regionalliga-season, but likewise had to file for bankruptcy the year after. Both clubs therefore found themselves down in the fourth division.

2000s – The struggles for both clubs didn’t end there. While Sachsen initially had another quick stint in the Regionalliga for the 2003/04 season, VfB Leipzig was dissolved after their second insolvency in 2004. As a response, fans founded 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig, the name and logo being identical to the old GDR team from 1966. While the new club absorbed the old VfB youth teams, their senior team started all the way back in the lowest division. After securing promotion every time in their first four seasons, they quickly found themselves to be back in the fifth division.

Over in Leutzsch, other issues surfaced. A supporters group, founded all the way back in 1997 under the name of Ballsportfördergemeinschaft Chemie Leipzig (a.k.a. BSG Chemie, see what they did there?) began to grow increasingly dissatisfied with the club. The board moved their matches to the unpopular Zentralstadion, while supporters also protested heavily when Red Bull tried to set foot in the city for the first time and takeover the club in 2006. The straw that broke the camel’s neck were the increasing political disputes within the club and it’s fan scene that culminated in physical assaults in November 2007 during an away game in Sangershausen. As a response, the supporters group decided to part ways with FC Sachsen Leipzig and instead found their own club, much like fans had done over in Probstheida a few years earlier. This lead to disputes about who the real successor of old GDR-Chemie was. While FC Sachsen possessed all claims to the legal line of succession, the new BSG Chemie Leipzig had the name, stadium and almost the same badge of the old club from the fifties. Still, FC Sachsen Leipzig had bigger problems, as another insolvency relegated them to the fifth division, meeting up again with Lok.

Enter Red Bull. After neither FC Sachsen Leipzig nor any other German clubs were willing to entertain their ideas of a Red Bull takeover, they turned to SSV Markranstädt, a club from a suburb of Leipzig with a fifth division team. They made a deal: For the 2009/10-season, all teams of Markranstädt would run as RB Leipzig. After the season, Markranstädt would get back all teams bar the top one, plus some extra money as a bonus. At the request of the Saxonian Football Association, they also took over some youth teams from the bankrupt FC Sachsen Leipzig. Therefore, three clubs from the city participated in the 2009/10 Oberliga Sachen. RB dominated the league, finishing 22 points ahead of second place, while FC Sachsen, now back again at the Adolf Kunze Sportpark in Leutzsch, finished 6th and Lok 12th. Even then, the old clubs still pulled impressive crowds, with almost 15,000 spectators for the derby between Sachsen and Lok.

2010s –In the following season, RB Leipzig made a similar deal with ESV Delitzsch like they had with Markranstädt in order to also have a second team. Meanwhile, FC Sachsen entered a controversial partnership for youth development with RB. Combined with terrible performances in the second half of the season, specator numbers collapsed, leading to yet another insolvency in 2011 (see a pattern here?). This time, FC Sachsen didn’t survive and was disbanded, with youth and amateur teams taken over by a new club called SG Leipzig-Leutzsch. Two years later, they changed their name to SG Sachsen Leipzig (what is it with those name changes all the time?), and another year after that, the whole club was disbanded again after the fourth insolvency since 2001. I hope you are as unsurprised as I am. Another new club called LFV Sachsen Leipzig was founded shortly thereafter. They currently play in the 9th division and share a ground with SV Nordwest Leipzig, one of the descendants of the old ZSG Industrie from all the way back in the 50s. But hey, at least they aren’t bankrupt yet.

Fan-founded BSG Chemie meanwhile rose through the ranks. After starting all the way down in the 12th division in 2008, they partnered up with VfK Blau-Weiß Leipzig for a season and today are back in the fourth division, still playing in the Alfred-Kunze Sportpark in Leutzsch. Their biggest success was their victory in the Sachsenpokal in 2018, which also was their ticket for next years DFB-Pokal, where they beat second division team Jahn Regensburg in the first round before being eliminated by SC Paderborn. It was pretty much the first time this club had done anything impressive since their cup win in 1966.

1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig also currently play in fourth tier at the Bruno-Plache-Stadion. Even though they’re by all measures the legitimate successor of VfB Leipzig, Lok are currently making efforts to officially merge with the technically still existing VfB. This would not only grant them some tax benefits, but also possibly allow them to wear a star on their jersey, signifying the titles of the old pre-war VfB Leipzig back in the early 1900s.

Another thing that shouldn’t go unmentioned is the fact that both Chemie and Lok have a clear political image at least since the early 2000s. It’s almost a bit disingenious to fit all of this into a single paragraph, when it’s in fact one of the biggest reasons why RBL succeded, but this text is long enough already. While both clubs try to distance themselves from any political extremism, their influence on individual supporters is limited. Diablos Leutzsch, the biggest ultra group of Chemie is often linked with the local antifa, while the club often plays friendlies against local clubs like the antifascist Roter Stern Leipzig, and thus is fairly popular with the political left. Lok meanwhile often made the news with racist and neo-nazi fans, with tifos like “Rudolf Heß – our Right Winger” and scarves that read “Juden Chemie” presented at derbies. Although the board and some supporter groups try to take a stand against racism, this is pretty much an uphill struggle and thus, Lok is seen as the right-wing club of the city. Especially derbys’ between the two aren’t exactly the games where you’d bring your family to the stadium.

The story of RB Leipzig is well known. They rose through the leagues and currently are one of the top Bundesliga teams. One thing is undeniable though: As a club without any political positioning and no appeal to any ultra groups of any kind, they are the preferable choice for the family of four who just want to spend a nice evening, eat overpriced sausages and watch some of those footballers play they only saw on TV before.

So there you have it. A historical analysis about why there was such a power vacuum for Red Bull to slip into and base their team in Leipzig. To explain the city’s footballing history, you need to talk about 25 different clubs. The problem becomes especially noticeable when we compare Leipzig with Dresden for the last time. If we draw a similar diagram for Dynamo Dresden like we did for Leipzig before, we can see that, bar some changes to name and logo, the club’s history has been pretty straightforward since the mid-50s, and most importantly, without any bankruptcies (Not to say they didn’t come close sometimes).

When Chemie/Sachsen and Lok/VfB struggled both sporting-wise and financially and competed for fans at the same time, Red Bull was there to pick up the pieces and rise to the top, while the old clubs were often more invested in fighting with each other rather than building professional structures.

Recent Comments