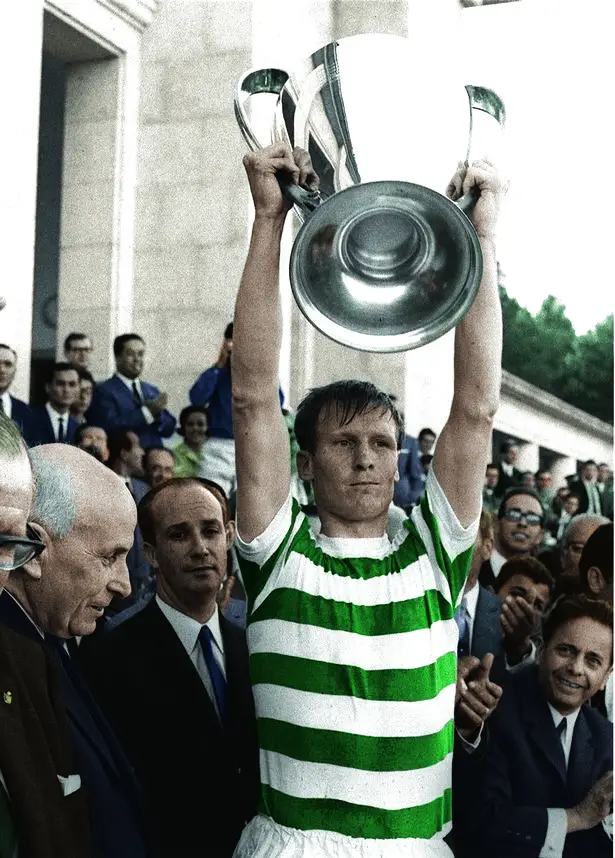

EVEN if Billy McNeill was really nicknamed Cesar rather than Caesar, there was no denying that the scene on May 25, 1967, was one of imperial grandeur and triumph.

The big Celtic captain could have been a victorious gladiator in a Roman amphitheatre as he stood high in the Estadio Nacional, holding the gleaming European Cup above his head as the early evening Lisbon sun reflected off it.

Jock Stein’s legion had put paid to the barbarity of Helenio Herrera’s ultra-defensive Catenaccio system. “Unbeatable” Inter Milan, who had conceded only three goals in the nine matches leading up to the final, had been unable to contain Celtic’s free-flowing attacking game. Their famed security chain was sheared, and they lost 2-1.

Yet, within less than five months the glory of that day had been swept away. The glint on the European Cup swiftly faded as beautiful football was dragged into the shadows by a new phenomenon — a diabolical Argentinian invention called antifutbol.

There had been glimpses of it when England met Argentina in the quarter-finals of the 1966 World Cup. The South Americans fouled continually, causing Sir Alf Ramsey to make his famous comment: “We have still to produce our best football. It will come against a team who come to play football and not act as animals.”

However, antifutbol made its first unadulterated appearance before British eyes when Celtic met Racing Club of Buenos Aires in the Intercontinental Cup — the unofficial world club championship play-off. Racing Club were vicious enough over two legs, but it was in the third and deciding match, played in the Estadio Centenario in Montevideo, that they gave up any pretence of abiding by the rules and set out to chop down and intimidate Celtic’s players at every opportunity.

Even though four Scots and two Argentinians were sent off, Tommy Gemmell was still able to take his own below-the-belt retribution on Humberto Maschio who, he said, had come across the defence and “spat in all our faces”.

Jimmy Johnstone condemned Racing Club’s display as total hooliganism, while McNeill said: “They just went in for thuggery. They didn’t care which way they won. They were going to win at any cost.”

It seemed that football could fall no further, but the following year, against Manchester United, Estudiantes de La Plata dragged it down to new and uncharted depths. Under the management of Osvaldo Zubeldia, they became the living embodiment of this cynical system.

Antifutbol was created as a reaction to Argentina’s exit from the 1958 World Cup when they finished bottom of group one. Until then, the country had embraced a type of play called la nuestra — “our style” — which was all about skill and flair. Failure in Sweden, and particularly a 6-1 defeat to Czechoslovakia in Helsingborg, suddenly had Argentinians questioning themselves. Their belief that their football was superior to the rest of the world was dented. Changes had to be made.

At first, this desire for something different manifested itself in a more regimented system based on European discipline. Defence and man-marking began to take precedence over all-out attack. As Jonathan Wilson puts it in his book “Inverting the Pyramid”, the reaction against la nuestra was brutal. It spread through the whole of Argentinian football like a poison and from there into the national team. But it was Estudiantes who fashioned the sharpest hatchet and made antifutbol standard fare.

Zubeldia was a disciple of Victorio Spinetto, a highly-regarded coach who had rejected la nuestra as ineffective many years before the failure in Sweden. Zubeldia played for Spinetto at Velez where he was converted from attacking inside-left into a hard-working midfielder. He came to share his coach’s belief that whatever a team’s technical merits, there were worthless without attitude, teamwork and most of all toughness.

“You don’t arrive at glory through a path of roses” was Zubelidia’s philosophy, but he went further. He studied opposition teams in minute detail, looking for weaknesses. And he offered them no comfort. Playing Estudiantes was a miserable experience off the field as well as on.

When Zubeldia went to La Plata in 1965 Estudiantes were a modest provincial outfit generally preoccupied with avoiding relegation. Argentinian football was dominated by five sides from metropolitan Buenos Aires — in fact no club from outside the capital had ever won the championship — but Zubeldia’s upstarts quickly put an end to that. They won their first title in 1967 and were immediately acclaimed by the country’s new military dictator, Juan Carlos Ongania, who had reorganised football with the express hope of breaking the Buenos Aires stranglehold.

By winning the 1967 championship Estudiantes qualified for the Copa Libertadores. They won it in 1968 by beating Brazilian club Palmeiras, and that set up their infamous Intercontinental Cup encounters with Matt Busby’s Manchester United.

Estudiantes won, but their behaviour over the two legs led Brian Glanville to describe the so-called world club championship as “that most repugnant and expendable of competitions”. In the 1970 World Football Handbook he added that it once more supplied incidents which disgraced the game of football. The Daily Mirror went further, describing the match in South America as the night they spat on sportsmanship.

United’s combative Scottish striker Denis Law, who wasn’t exactly known for turning the other cheek, said in his 2003 autobiography “The King”: “That first leg was a truly frightening experience. It was the worst match I ever played in, without a doubt. It wasn’t about football. It was about war.”

This was possibly the high (or should that be low?) watermark of antifutbol. In the following year’s Intercontinental Cup, where they met AC Milan, Estudiantes went too far even by their own violent standards. Having lost the first leg 3-0 in Italy, they tore into Milan like a pack of crazed hounds when they got back to home turf. The second leg was no battle, as had taken place between Racing and Celtic in Montevideo. It was the Bombonera Massacre.

Pierino Prati was left concussed. Gianni Rivera was repeatedly punched by goalkeeper Alberto Poletti and then kicked to the ground by Eduardo Manera. But the Argentina-born France international Nestor Combin was singled out for particularly vicious treatment. An elbow from Ramon Aguirre Suarez shattered his cheekbone and nose. Pictures show him stretched out semi-conscious, his white kit dyed red by his blood. Yet despite the carnage, Estudiantes failed to retain the cup.

The public mood rejected Zubeldia and his methods. As Jonathan Wilson puts it: “a wave of revulsion was unleashed.” The Argentinian newspaper El Grafico commented: “Television took the deformed image of a match and transformed it into urban guerrilla warfare.” Even the military dictator, Ongania, voiced his disgust.

Estudiantes’s hold on the game was broken. Their period of dominance was almost over and after losing to Feyenoord in 1970 they would never again play off for the Intercontinental Cup. After years of destroying the opposition, antifutbol had destroyed its chief exponent.

Recent Comments