Some people are etched in our collective minds, as are some legends and indeed, perceptions about such words and legends. When it comes to football, skillful build-up and continuous passing is the way really to play according to millions over the world. If you keeping winning 1-0 over and over, you’re parking the bus. If you invented ‘catenaccio’, you are killing football. Because it’s not as breath-taking as a triangle to beat burly defenders. Because it seems to be ordinary, pedestrian. But the fact remains, not everyone can ‘catenaccio’ their way to titles. A certain Helenio Herrera did, some 50 years back. Footballing history hasn’t been as kind to him as someone with his titles deserved. Yet Herrera or ‘catenaccio’ can’t be ignored, its legacy aflame despite its almost unilateral infamy. Perhaps that’s because it was successful, more than perhaps it was expected to by experts and inventors alike. Why then has ‘catenaccio’ had the distinction of being hated and imitated in equal measure?

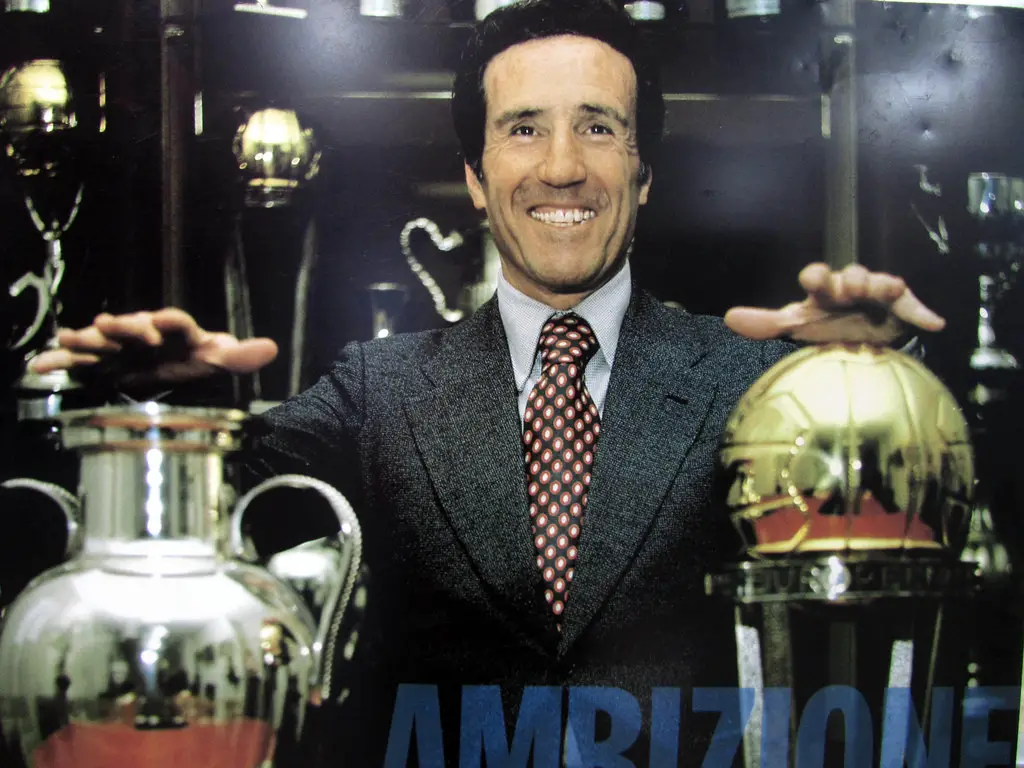

When discussing this tactic, it’s impossible to not dwell upon the man it’s most strongly and repeatedly attributed to, Helenio Herrera. It’s interesting that Herrera is spoken of in the most glowing terms in today’s football scenario where effectiveness is the catchword and silverware justifies the means. But back in the good ol’ days, Herrera was reviled and considered to be the incarnation of Satan in the many football churches of the world. He was slammed by the same football journalists, after his crowning glory, as the ones who gave him the title ‘il mago’ or ‘the magician’ at the outset of his coaching career in Italy.

‘Catenaccio’ literally means door-bolt or lockdown, depending upon lingual interpretation. The implication doesn’t change though. Unanimously considered to be the most effective and innovative defensive strategy ever-devised, it was immortalised by Herrera’s Internazionale of the 1960s. They were called Grande Inter by their fans due to their tremendous success in that period in which they were able to win three Scudettos, two consecutive European Cups and, perhaps most crucially for those very fans, able to completely overshadow their illustrious neighbour A.C. Milan for a prolonged period of time. This was the device that Herrera used to eke out 1-0 wins against the strongest of attacks, most notably the 1965 Benfica which boasted of the marvellous Eusebio among others.

Interestingly though, for their almost synonymous connection, Herrera and ‘catenaccio’ didn’t have a singular journey. In fact, it’s easy to forget that the tactic and most of its features actually started out almost two decades before that famous night in San Siro when it reached its pinnacle. Instead an Austrian trainer named Karl Rappan should be credited with that. Interestingly, the reason that the tactic was developed by Rappan was that he led a semi-professional team which was physically and technically incapable of challenging the professional teams of 1930s Switzerland. Herr Rappan consequently decided that he needed a tactical set-up to neutralise this disadvantage that his charges were always going to be in. The set-up was remarkably successful and that catapulted Karl Rappan to the Swiss National Team and the ‘verrou’ (Austrian for bolt) to international cognition. Rappan’s ‘verrou’ was basically a defensive modification of the erstwhile ubiquitous 3-2-5 formation, often called the ‘WM’ formation. In the ‘WM’, three players played in defence to begin with but one of these usually moved up to reinforce the midfield upon gaining possession. As expectable, this formation was susceptible to fast counter-attacks against teams with technical and fast players and midfielder who could pick long passes. This was modified by Rappan whereby he added one more player to the backline. This player in fact went behind the line of defence and thus, became the last block of defence preceding the goalkeeper. This extra player, called ‘verrouilleur’ by extension, had an adaptive role which depended upon the state of the game or the opposing personnel. Depending upon the same, the player could be asked to man-mark a specific forward, double-team an opposing winger or simply sweep behind the defence to limit the risk of players running though on goal. As intended by Rappan, this negated the scope for individual influence in a game, as was common in those days in terms of the forward play of most teams.

While Karl Rappan was charting his success story with these tactics at the helm of Servette, Grasshopper and the Swiss national side, Helenio Herrera was leaving his imprint upon the Spanish League following his time at the French League. Herrera was the coach of numerous teams in Spain during the 50s. His major achievement was leading Atletico de Madrid and FC Barcelona to consecutive league crowns during the 1949-1951 and 1958-1960 periods respectively. Journalistic sources suggest he did this in as expansive a style as was in vogue in those days. In fact his Barcelona days produced an average of 91 goals per season which compares favourably with the supposedly all-conquering Real Madrid outfit of the same time which boasted of Di Stefano and Puskas. His successes led Internazionale to appoint him as the manager at the start of the 1960-61 season. It’s rumoured that Internazionale’s attempt to extend their carefully projected global image and Latin American leanings were a part of the decision.

This was the start of a hugely successful 8-year association but one, whose progress was ironic to say the least. As it happens, ‘catenaccio’ as a strategy wasn’t introduced to Italy by Herrera. Instead it’d been applied with exceptional results by Nereo Rocco, one of the most famous names in Italian football. Rocco employed the tactic to lead his decidedly mediocre Triestine side to a stunning second place in the 1947-48 title chase. After moving jobs a few times, he reproduced the magic at an equally unfancied Padova in the mid-50s. Beating the drop in Serie-B, Padova won promotion to the top division and went on to secure the third spot as well with a very small squad of players. What followed in the following decade though was all that contributed to the legend of ‘catenaccio’.

The 1960-61 season was a bitter pill to swallow for Helenio Herrera. His team played a possession-based offensive style of football but could only finish third in the Serie-A. They were the second best attack in terms of the number of goals but often suffered due to an inability to hold onto leads, especially away from home. The season also involved a 9-1 thrashing at the hands of Juventus in Derby d’Italia following Inter’s decision to protest the scrapping of the original match by fielding youth team players. In later years, Italian journalists attributed Herrera’s adoption of ‘catenaccio’ to that defeat and his inability to affect that result tactically. The next season was another bitter pill for him as his team finished second to bitter rivals A.C. Milan who won with a defensively oriented playing style, in their away games, that their newly appointed manager had previously used with great effect too. Their new manager that season, Nereo Rocco.

Next season, Herrera adapted his backline to a more pragmatic format. His inspiration quite possibly was the successful side that Rocco’d built previously. He switched Armando Picchi to a sweeper role in the most glaring change. This way Pichhi held a free role, which came to be known as the ‘libero’ role later, and covered the goal as an extra line of protection. But this was where Herrera’s tactics started varying from Rocco’s. Unlike Rocco, Herrera set up his team in a formation which can loosely be considered to have been a 5-3-2. But assigning the simplicity of this specified formation would be doing a disservice to Herrera.

Herrera’s team was built on the principles of a team effort and strong work ethic. Organisation was of prime importance whereby his team set out in the shape of 4 levels. These were: first level of a sweeper, two/four defenders depending upon the possession, five/three midfielders and two forwards. The forward line of 2 was amorphous in which Sandro Mazzola played a vital role, that of the ‘fantasista’. Blessed with sensational touch and explosive pace and finishing to match, Mazzola was the man responsible for netting every half-chance, especially away where he’d often be stuck on his own, but equally importantly, setting up his more advanced partner. He was usually paired with the lethal Benianimo Di Giacomo. In the midfield, the cannibalistically named Luis Suarez Miramontes was the playmaker responsible for finding the men upfront. But true wonders of this team and Herrera’s system were the two players on the wings.

Contrary to popular belief, Herrera did NOT park a bus. The connotation can be attached to setting up of parallel lines of players designed to stifle the opposition’s flair at the cost of mobility. Something that Jose Mourinho, for better or for worse, is a master of. Herrera did not do that. True, the team set up with organized lines to maintain a fixed shape. But Herrera did not sacrifice fluidity for this. Instead he innovated and set up a position which can best be described as a half-back. On the right, the Brazilian Jair da Costa was a convert from a forward. His role was to charge forward whenever possession was won. In fact, Jair was the outlet for Suarez, Corso, Zaglio and Pichhi whenever they won the ball. Of these, Suarez, Corso and Pichhi were particularly accomplished passers known for their range. This perfectly complemented Jair’s ability to drive forward. On the left wing was perhaps one of the world’s first example of an inverted winger. Though naturally left-footed, Giacinto Facchetti was renowned for cutting in and finishing. He scored 59 field goals from 450 odd appearances for Inter. This would be unmatched even today. Facchetti and Jair were the two players which provided balance and thrust to the Inter machine. They made sure that the team stayed organized with men behind the ball when the opposition had the ball, but also that this did not impede them when deciding to go forward.

Internazionale finished 1962-63 as the winners of the Scudetto, having conceded just 20 goals throughout the season compared to 35 the season before. It must be remembered thought that Inter remained fairly attacking at home, but away from home they progressively became ultra-defensive. Through the next five seasons this remained Herrera’s strategy, one which he especially used with devastating effect in cup competitions. Internazionale won the European Cu for the first time in their history the following season by beating Real Madrid 3-1 in the final and then were successful in defending it in 64-65. The 1964-65 season was in fact what established Herrera in football folklore. Inter’s route to the final had been anything but straightforward. They scraped past Ranger 3-2 in the quarters and then controversially beat Shankly’s Liverpool 4-3 in the semis having lost 3-1 at Anfield and having had dubious decisions in San Siro. In the circumstances, it was a surprise when the final was held at San Siro itself as they faced off against Eusebio’s all-Portuguese Benfica. It was a classic clash of the styles as the Black Pearl inspired team tried to overpower Inter with their swift interchanges and close control. Inter ceded a lot of the possession but were able to cope comfortably till the 43rd minute when Jair scored on a typical charge. What followed guaranteed infamy for Herrera and that team. Exploiting the back-pass rule, Inter players kept playing it back and into the hands of their ‘keeper Giuliano Sarti and attacking on the break occasionally. This was a tactic that Herrera used increasingly in later years.

Herrera left Internazionale in 1968 and had a frustrating spell with Roma where his tactics couldn’t get him the coveted prize again. His side finished top of the league for four consecutive seasons though they lost the 1963-64 crown to Bologna after a playoff. Herrera never won a league again after leaving Inter with only a Coppa Italia at Roma and a Copa del Rey at Barcelona in 1981. His decline coincided with the demise of ‘catenaccio’ as a concept. The advent of Rinus Michels’ ‘total football’ spelled doom for the man-marking based school of thought that Herrera preached mostly. His all-conquering Ajax beat Inter 2-0 in the European Cup final and then decimated Milan 6-0 the following year.

Football followed natural evolution. ‘Catenaccio’ was a brilliant innovation and supremely effective. It also necessitated the invention of the infinitely more favourably perceived ‘total football’. Even some concepts of the Herrera were adopted and adapted to brilliant effect by other sides. None more than Der Kaiser himself, Franz Beckenbauer became an overnight celebrity with his marauding runs from deep during 1966 World Cup. Yet, he was just the same libero. Just that he did more than sweep through balls, when he felt like it Beckenbauer swept his opponents off their feet too. He had the ability to add to Herrera’s machine. Likewise with fitter players and more inventive creators like Johan Cryuff in the game, it became difficult to handle the teams. The concept also was rooted in the time when long-range shooting was rare and thus, playing through a team was the only way to score. Gerd Mueller changed it with his screamers. The biggest factor though has been the change in the point-scoring system. While earlier a point went to a draw and two point were given for a win, nowadays three points are earnt by the winners. This more than anything else has led to teams going for a win, even on dreary away trips. But perhaps most interestingly, ‘catenaccio’ inspired generations of footballers in what it was meant to neutralise, individual brilliance. With the oppositions attempting to cut-off all passes and tight marking, some of the finest dribblers of the game honed their skills. Diego Maradona, Roberto Baggio, Alessandro Del Piero were some of the silky footballers who flourished in the Italian Serie-A which has still not shaken off its tag as the cradle of ‘negative’ and defensive football. Such has been the impact of Messrs. Rocco and Herrera.

Many managers have since tried to emulate the success of Helenio Herrera not but with comparable success. It helped that he was able to retain the core group of players, only making some effective additions like Joaquin Peiro in 1964. In fact, he particularly favoured his wing-players, once famously stating that when other coaches thought they could emulate his success by employing a Pichhi, they forgot that he also had a Facchetti. It is worth iterating that as a concept, ‘catenaccio’ was rooted in pragmatism and quite possibly. It has often been stated that players with virtues of Herrera’s Inter would have had a fair chance even with an expansive brand of football. It’s possible that Herrera failed to back the attacking prowess at his disposal. Whatever be the case, his success cannot be denied. Herrera’s also often called the first ‘superstar manager’. A lineage which has been continued by the likes of Michels, Cesare Maldini and more recently, Sir Alex Ferguson and Mourinho, managers who’ve been the face of their team. He was also the manager who introduced the concepts of monitoring the diet and retiring to a retreat before matches. His pep talks are said to have been legendary and many a quote is attributed to him. Among the negatives, he’s been accused of match-fixing and even causing the death of a player due to his strict training regimen. His organisation principles were showcased by many legendary managers of the game like Cesare Maldini who believed in his idea that you can’t lose a game where you don’t concede. Indeed three decades of Italian national sides were built on that philosophy with notable success. The country also gave some the world’s greatest defenders, from Paolo Maldini to Franco Baresi to Fabio Cannavaro to Alessandro Costcurta. It’s impossible to ignore Helenio Herrera’s legacy. It’s said he inspired Jose Mourinho’s style. Not least because ‘the special one’ shares the wizardry of predicting match and league results with Herrera. In the very least, Herrera’s teams were among the best in defence. And as a certain Mr. Rodgers would attest now, NOT anyone can even park the bus, let alone drive it to glory.

-Jayeek Chatterjee

5 Responses

Good stuff,i want to see more articles like this

Do you think mourinho is the modern herrera with his brilliant attention to detail especially when it comes to defending. Also why has the catenaccio disappeared?

Really nice article, tho there is a little mistake : “verrou” isn’t australian but french

“austrian”